Abstract

Introduction: Odontoid fractures represent a clinically significant subset of cervical spine injuries, with an increasing incidence among the elderly population. Understanding their demographic characteristics, fracture subtypes, and treatment outcomes is crucial for optimizing management strategies and guiding prevention efforts.

Methods: This retrospective study included 65 patients with odontoid fractures treated between 2018 and 2023 at a tertiary neurosurgical center. Fractures were classified according to the Anderson and D’Alonzo system and further subclassified using the Grauer classification for Type II fractures. Clinical data, including age, mechanism of injury, fracture subtype, treatment modality, and radiologic outcomes, were analyzed.

Results: The mean age of the cohort was 61.9 years, with 56.9% of patients aged ≥65 years. Low-energy ground-level falls were the most common mechanism of injury (50.7%), occurring predominantly in elderly patients. According to the Anderson and D’Alonzo classification, Type II fractures were the most frequent (53.8%), followed by Type III (44.6%). Among Type II fractures, 82.5% were Type IIB. Surgical treatment was performed in 33.8% of cases—most commonly anterior odontoid screw fixation—while 66.2% were managed conservatively. CT-based follow-up (n=42) demonstrated an overall osseous union rate of 76.1%. Fusion was achieved in 84.2% of surgically treated and 69.5% of conservatively treated patients. Patients younger than 65 years had a higher fusion rate (81.8%) compared with older patients (70%).

Conclusion: Odontoid fractures are predominantly geriatric injuries, most often resulting from low-energy ground-level falls. Type II fractures, particularly the IIB subtype, remain the most common and carry a higher risk of nonunion. Surgical fixation provides superior fusion rates compared to conservative treatment. These results emphasize the importance of patient-specific management and suggest that future studies should further refine treatment algorithms in light of evolving surgical techniques and demographic trends.

Keywords: odontoid fracture, C2 fracture, cervical spine, surgical fixation, osseous union

Introduction

The odontoid process of C2 plays a key role in atlantoaxial biomechanics, and fractures of this region represent a clinically important subgroup of cervical trauma.1 Odontoid fractures constitute nearly one-fifth of all cervical spine fractures in adults and are the most common fracture subtype in the elderly population (≥ 65 years).2,3 These fractures demonstrate a bimodal age distribution, with high-energy trauma—most commonly motor vehicle collisions—predominating in younger individuals, and low-energy falls being more frequent in elderly patients due to age-related bone density loss and degenerative changes.4 Improvements in road safety and vehicle engineering have reduced high-energy cervical trauma in younger populations, whereas population aging, particularly in Europe, has contributed to a rise in osteoporotic cervical spine injuries among older adults. 5,6

The choice of treatment is influenced by several factors, including fracture morphology, patient age, comorbidities, and the extent of displacement. Conservative treatment generally involves external immobilization using a rigid cervical collar or halo vest and is preferred in fracture patterns considered biomechanically stable. Surgical intervention, on the other hand, may be required in unstable configurations or when the likelihood of nonunion is high. Techniques such as anterior odontoid screw fixation or posterior C1–C2 fusion can be selected based on the patient’s clinical profile and specific fracture characteristics.7,8

The aim of this study is to evaluate the distribution of odontoid fracture subtypes and to analyze age- and etiology-related subgroup patterns. A clearer understanding of these distributions may support the development of more precise treatment strategies and targeted prevention measures. Identifying variations in fracture characteristics across different patient groups can also provide useful guidance for clinical decision-making. Furthermore, continued monitoring of these demographic trends will help clinicians adjust their management approaches in parallel with the evolving needs of an aging population.

Material and Methods

This retrospective study included patients who were diagnosed with odontoid fractures and treated between 2018 and 2023 at a tertiary neurosurgical center. Electronic medical records were reviewed to identify all patients who presented with a C2 fracture during this period. Patients with non-odontoid C2 fractures and fractures secondary to oncologic etiologies were excluded from the analysis. Demographic variables, mechanism of injury, fracture subtype, and treatment modality were recorded retrospectively.

All patients underwent cervical CT (computed tomography) imaging at presentation. Odontoid fractures were independently evaluated and classified by two experienced neurosurgeons according to the Anderson and D’Alonzo classification. Type II fractures were additionally subclassified using the Grauer system.9,10 In cases of disagreement, a consensus was reached through joint review. The minimum intended radiologic follow-up target was ≥12 months.

The final radiologic outcome was evaluated using cervical CT. Osseous union was defined as restoration of cortical continuity and visible trabecular bridging across the fracture line on CT. Absence of these findings was considered nonunion.

Results

A total of 110 patients with C2 fractures were evaluated in our clinic between 2018 and 2023. Among them, 65 patients (59%) had odontoid fractures and were included in the final analysis. The mean age of these patients was 61.9 years (range: 15–100), and 37 patients (56.9%) were ≥65 years old. The most common trauma mechanism was low-energy trauma. Falls from the ground level were observed in 33 patients (50.7%), followed by motor vehicle accidents in 21 patients (32.3%), falls from height in 7 patients (10.7%), diving injuries in 2 patients (3%), and other causes in 2 patients (3%). Only 3 of the 33 ground-level fall patients (9.09%) were younger than 65 years.

According to the Anderson and D’Alonzo classification, 1 patient (1.53%) had type I, 35 patients (53.84%) had type II, and 29 patients (44.61%) had type III fractures (Figure 1). Based on the Grauer subclassification of type II fractures, 3 patients (8.5%) were type II A, 29 patients (82.5%) were type II B, and 3 patients (8.5%) were type II C (Table 1).

| Table 1. Distribution of odontoid fractures according to the Anderson–D’Alonzo and Grauer classifications | ||

| Fracture Type |

|

|

| Type I |

|

|

| Type II |

|

|

| IIA |

|

|

| IIB |

|

|

| IIC |

|

|

| Type III |

|

|

| Total |

|

|

Among the 65 odontoid fracture patients, 22 (33.8%) underwent surgical treatment, and 43 (66.2%) were treated conservatively (Table 2). Surgical intervention was performed in 20 of 35 type II fractures (60%) and in 3 of 29 type III fractures (10.35%). One patient with a type I fracture received conservative treatment.

| Table 2. Distribution of treatment modalities and surgical techniques in patients with odontoid fractures | ||

| Parameter |

|

|

| Total patients |

|

|

| Surgical treatment |

|

|

| Conservative treatment |

|

|

| Type II fractures operated |

|

|

| Type III fractures operated |

|

|

| Type I fractures operated |

|

|

| Surgical techniques (n = 22) | ||

| Anterior odontoid screw fixation |

|

|

| Posterior C1–C2 fusion |

|

|

| Combined approach |

|

|

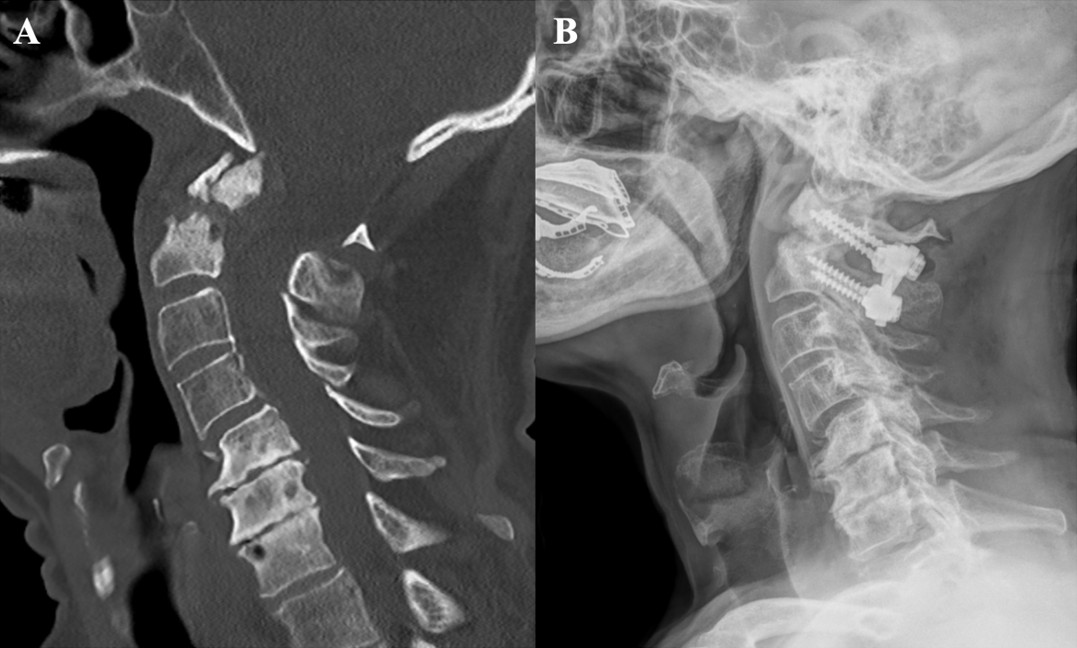

Among surgically treated patients, 13 (59%) underwent anterior odontoid screw fixation (Figure 2), 7 patients (31.8%) underwent posterior C1–C2 fusion (Figure 3), and 2 patients (9%) were managed with combined anterior + posterior approaches (Table 2).

The final radiologic outcome was evaluated using cervical CT at a minimum of 12-month follow-up. Six patients who died within the first year of follow-up, as well as seventeen patients who could not be reached at the 1-year control visit, were excluded from the fusion outcome assessment. Therefore, CT-based fusion analysis was performed on 42 patients with available radiologic follow-up.

Among 42 odontoid fracture patients with assessable CT follow-up, union was observed in 32 patients (76.1%) and nonunion in 10 patients (23.9%). By fracture subtype, union occurred in 1/1 (100%) type I, 16/23 (69.5%) type II (2/2 type IIA, 12/19 type IIB, 2/2 type IIC), and 15/18 (83.3%) type III fractures. When stratified by treatment, CT-based union was achieved in 16/19 surgically treated patients (84.2%) and 16/23 conservatively treated patients (69.5%).

Age stratification demonstrated that union was achieved in 18/22 (81.8%) patients younger than 65 years, compared with 14/20 (70%) in patients aged ≥65 years.

Discussion

The findings of this study reinforce the growing recognition that odontoid fractures represent a predominantly geriatric injury pattern. The mean age of the cohort was 61.9 years, and more than half of the patients were aged ≥65 years, reflecting the high prevalence of these injuries among older adults. In contrast to the high-energy trauma mechanisms typically observed in younger adults, low-energy ground-level falls were the predominant cause of odontoid fractures among elderly patients in our series, accounting for 91% of cases. This trend is consistent with the age-related shift toward low-energy trauma mechanisms reported in the literature and likely reflects the combined impact of frailty and postural instability, highlighting the need for targeted fall-prevention strategies and heightened clinical awareness in this population.11,12

In our cohort, Type II fractures constituted the majority of odontoid injuries, followed by Type III fractures, a distribution consistent with previous epidemiological studies.4,13,14 The predominance of Type II fractures reflects the intrinsic biomechanical weakness of the odontoid base, where cortical support is limited and vascularity is reduced.15 According to the Grauer classification, most Type II fractures in our series were identified as the IIB subtype. In our series, approximately one-third of all odontoid fractures and 60% of Type II fractures were managed surgically, most commonly with anterior odontoid screw fixation.

The overall osseous union rate in our study was 76.1%, which is in line with the outcomes reported in the literature.12,16-18 Surgical management resulted in higher fusion rates than conservative treatment (84.2% vs. 69.5%), supporting the view that internal fixation enhances mechanical stability and facilitates bone healing. Most nonunion cases were observed in Type II fractures, reflecting their biomechanical susceptibility to instability. Age also appeared to influence healing potential, as osseous union was achieved in 81.8% of patients younger than 65 years compared with 70% in older patients. Overall, these results suggest that fracture configuration and patient characteristics are key determinants of fusion outcomes.

This study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Its retrospective and single-center design may limit the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, the present findings provide valuable insight into the demographic characteristics, fracture distribution, and treatment outcomes of odontoid fractures across different age groups. The results emphasize the importance of individualized treatment strategies that consider patient age and fracture morphology and highlight the need for prospective multicenter studies to further refine management algorithms.

Ethical approval

Ethical committee approval was not required for this study as it was a retrospective analysis of anonymized patient data.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Akobo S, Rizk E, Loukas M, Chapman JR, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. The odontoid process: a comprehensive review of its anatomy, embryology, and variations. Childs Nerv Syst 2015; 31: 2025-2034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-015-2866-4

- Salottolo K, Betancourt A, Banton KL, et al. Epidemiology of C2 fractures and determinants of surgical management: analysis of a national registry. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2023; 8: e001094. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2023-001094

- Fredø HL, Rizvi SAM, Lied B, Rønning P, Helseth E. The epidemiology of traumatic cervical spine fractures: a prospective population study from Norway. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012; 20: 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-20-85

- Baranto D, Steinke J, Blixt S, et al. The epidemiology of odontoid fractures: a study from the Swedish fracture register. Eur Spine J 2024; 33: 3034-3042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08406-3

- Bruggink C, van de Ree CLP, van Ditshuizen J, et al. Increased incidence of traumatic spinal injury in patients aged 65 years and older in the Netherlands. Eur Spine J 2024; 33: 3677-3684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08310-w

- Yokogawa N, Kato S, Sasagawa T, et al. Differences in clinical characteristics of cervical spine injuries in older adults by external causes: a multicenter study of 1512 cases. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 15867. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19789-y

- Joaquim AF, Patel AA. Surgical treatment of Type II odontoid fractures: anterior odontoid screw fixation or posterior cervical instrumented fusion? Neurosurg Focus 2015; 38: E11. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.1.FOCUS14781

- Nouri A, Da Broi M, May A, et al. Odontoid fractures: a review of the current state of the art. J Clin Med 2024; 13: 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13206270

- Anderson LD, D’Alonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974; 56: 1663-1674.

- Grauer JN, Shafi B, Hilibrand AS, et al. Proposal of a modified, treatment-oriented classification of odontoid fractures. Spine J 2005; 5: 123-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2004.09.014

- Ochoa G. Surgical management of odontoid fractures. Injury 2005; 36(Suppl 2): B54-B64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2005.06.015

- Charles YP, Ntilikina Y, Blondel B, et al. Mortality, complication, and fusion rates of patients with odontoid fracture: the impact of age and comorbidities in 204 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2019; 139: 43-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-018-3050-6

- Robinson AL, Möller A, Robinson Y, Olerud C. C2 fracture subtypes, incidence, and treatment allocation change with age: a retrospective cohort study of 233 consecutive cases. Biomed Res Int 2017; 2017: 8321680. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8321680

- Robinson AL, Olerud C, Robinson Y. Epidemiology of C2 fractures in the 21st century: a national registry cohort study of 6,370 patients from 1997 to 2014. Adv Orthop 2017; 2017: 6516893. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6516893

- Dong WX, Ma W, Xu N, Hu Y. Odontoid base hypodensity and its role in type II fracture risk and nonunion: a CT study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2025; 26: 1023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-025-09268-6

- Meyer C, Oppermann J, Meermeyer I, Eysel P, Müller LP, Stein G. Management and outcome of type II fractures of the odontoid process. Unfallchirurg 2018; 121: 397-402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-017-0428-9

- Di Paolo A, Piccirilli M, Pescatori L, Santoro A, D’Elia A. Single institute experience on 108 consecutive cases of type II odontoid fractures: surgery versus conservative treatment. Turk Neurosurg 2014; 24: 891-896. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.9731-13.0

- Reinhold M, Bellabarba C, Bransford R, et al. Radiographic analysis of type II odontoid fractures in a geriatric patient population: description and pathomechanism of the “Geier”-deformity. Eur Spine J 2011; 20: 1928-1939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-011-1903-6

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.